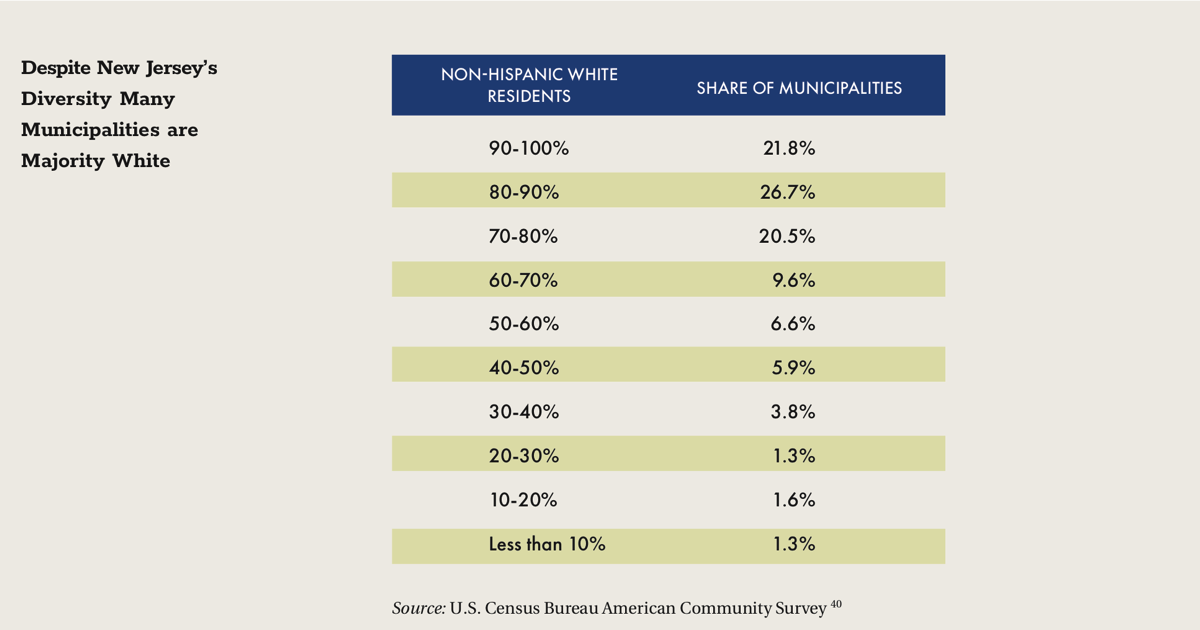

Although New Jersey is one of the nation’s most diverse states, with African-American, Latino, and Asian residents making up 44% of the population (the national average is 38%), its residents face high levels of socioeconomic and racial segregation that are grounded in patterns of housing segregation.38 These housing patterns, in turn, result in high levels of racial and socioeconomic segregation in school districts, given that most New Jersey school districts conform to municipal boundaries. As a result, most black and Latino students in New Jersey attend schools where the share of low-income students is more than three times the share of low-income students in the school of a typical white student.39

New Jersey’s schools are now among the most segregated in the country, with urban schools enrolling mostly African-American or Latino students, while suburban schools remain mostly white. In the 20 years between 1989-90 and 2010-11, the state’s proportion of “intensely segregated” schools (90% to 100% minority students) increased to 18.7% from 11.4% and so-called “apartheid schools”—schools where 99% of the student population is African-American or Latino— grew to 8% from 4.8%. Today, 26% of African American and 13% of Latino students in New Jersey attend one of those “apartheid schools.”41

New Jersey’s pattern of segregation is a corollary to the exclusionary land-use regulations that were observed in 1975 in the Mount Laurel I decision and continue today. Despite the important progress made as a result of the Fair Housing Act of 1985 and the Mount Laurel decisions, municipal land-use zoning statewide has resulted in a land-use pattern that has become substantially more segregated and sprawling than in 1970.42 These dynamics create communities where poverty is concentrated, educational and economic opportunities are scarce, and upward mobility is limited.

Over the years, New Jersey has made significant attempts to both combat segregation and make home ownership and renting more affordable. The New Jersey Supreme Court’s groundbreaking Mount Laurel rulings in 1975 and 1983 required municipalities to use their zoning powers to promote (rather than, as many had, restrict) opportunities to produce homes affordable to low- and moderate-income households.43

Mount Laurel II put teeth in the original doctrine by imposing the builder’s remedy, under which the court removes zoning powers for a particular property from non-compliant municipalities and provides higher density and other zoning relief to the builder in exchange for the provision of a mandatory affordable housing set-aside. Mount Laurel II also set the stage for development and implementation of a fair share methodology that allocates housing obligations to municipalities based on their share of the region’s wealth, jobs/ratables, and their capacity for growth in accordance with the State Plan. The decision led in 1985 to both the State Planning Act, establishing the State Planning Commission and Office of State Planning to produce the State Development and Redevelopment Plan, and the Fair Housing Act.

Key to the vision reflected in the State Planning Act is an ample supply of homes that meet local, regional, and state needs. With an inclusive and coordinated planning process, municipalities, counties, and the state collaborate to ensure housing choice as well as to share the benefits and costs associated with producing a range of housing options. Nonprofit organizations and the private sector, often working together, bring valuable capacity and produce homes consistent with public plans and decisions.

The Fair Housing Act created the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH) to assess the statewide need for affordable housing, allocate that need on a municipal fair share basis, and review and approve municipal housing plans aimed at implementing the local fair share obligation. At least 65,000 affordable homes were produced during 1980-2014 under Mount Laurel and the Fair Housing Act and at least 15,000 existing homes were rehabilitated.44 Implementation had stalled, however, until recently.

COMPLETING THE LEGAL PROCESS

Today the courts again have stepped in. The 2015 Mount Laurel IV decision broke through political-administrative gridlock by sidestepping a “moribund” COAH and returning enforcement of the Mount Laurel doctrine to state trial court judges. As a result, courts have returned to the role established under Mount Laurel II and are again hearing cases and making decisions on individual municipal fair share obligations and compliance plans.

Most recently, a statewide need has been identified for more than 280,000 additional homes for low- and moderate-income households by 2025.45 Taking proactive steps to meet this need is critical if New Jersey is to be a good place for people of all incomes to raise a family.46

More than 120 municipalities have reached agreements with fair housing advocates, developers, and civil rights leaders addressing fair share obligations for more than 36,000 homes for working families, seniors, and New Jerseyans with disabilities. These settlements can revitalize New Jersey’s many historic downtowns by fostering development near transit options. Many of these agreements also fight blight and sprawl by turning vacant office parks, strip malls, and industrial sites into vibrant new residential developments.

More towns are expected to negotiate settlements to establish their housing obligations, and judges are moving to establish the obligations for other municipalities.

RECOMMENDATION

The New Jersey Supreme Court in its Mount Laurel IV decision established a legal process, now underway in the trial courts, to ensure municipalities address their fair share of local and regional affordable housing need through 2025.

During the period in which this legal process is ongoing, the state should provide towns with tools to expedite construction, such as preferential treatment in applying for funds and increased support for creating homes. The state also should begin planning for a new fair share housing process that will prepare for future needs beyond 2025.

LEVERAGING FEDERAL POLICY

A rule adopted by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2015 provides the first guidance on federal Fair Housing Act obligations for local jurisdictions that accept HUD resources. Under its Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule, HUD directs jurisdictions to take “meaningful actions to overcome historic patterns of segregation, promote fair housing choice, and foster inclusive communities that are free from discrimination.”47 The federal Fair Housing Act has contained these provisions since 1968, but this was the first time HUD adopted an implementing rule.48

Nationally, 22 jurisdictions were ordered to comply with the rule in its first year, 100 more are submitting compliance plans, and still more have publicly committed to its guidelines even if the rule, which may be under threat from the current administration in Washington, is weakened or rescinded.49 In New Jersey, almost all jurisdictions receiving federal funds (the state, most counties, and some cities) will be required to submit such plans over the next three years.

RECOMMENDATION

To address chronic challenges that make our diverse state so segregated, New Jersey should press the federal government to maintain, and public jurisdictions in New Jersey to comply with, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule and provide incentives to jurisdictions that adopt and implement inclusive, equitable policies.

The state can take steps to provide fair housing resources for residents, regardless of what the federal government does, by pursuing aggressive enforcement of fair housing violations through the New Jersey attorney general’s Division of Civil Rights. New Jersey also should expand initiatives to promote regional mobility, including the state Department of Community Affairs program that annually offers 100 households rental housing vouchers coupled with housing counseling services to find rental homes in areas with good schools, jobs, and transit access.50

Re-establish the New Jersey Office of the Public Advocate with fair housing issues as one of its key mandates.

New Jersey should be on guard against attempts to weaken or dismantle the AFFH rule and should develop strong standards that include restoring the state Office of the Public Advocate as a strong, independent watchdog. Its mission would include serving as a champion of fair housing issues.