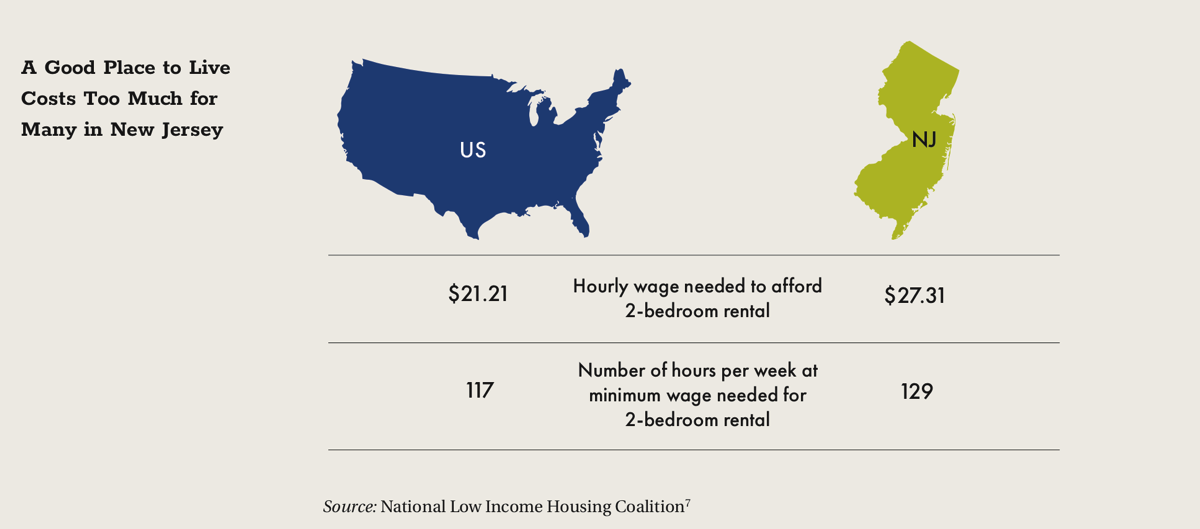

New Jersey’s foreclosure rate is 2½ times the national average.3 Apartment rents are the sixth most expensive in the country.4 More than 343,000 of New Jersey’s 1.1 million tenant households spend at least half of their pre-tax income on rent and utilities, making the state second only to Florida in the percent of the population in this situation.5 New Jersey’s “housing deficit” is most severe for those who struggle most to make ends meet. In 2016, only 29 affordable apartments were available for every 100 families making less than $30,000 a year.6

The state’s housing availability and affordability crisis prevents residents from meeting their other needs. In New Jersey, in 2014, the average family of four needed to bring in $32 an hour to cover the typical monthly “Household Survival Budget” of $5,348, which included average monthly housing costs of $1,257. Adjusting for household size, 37% of New Jersey households earn below the ALICE (“Asset Limited Income Constrained Employed”) Household Survival Budget.8

Perhaps not surprisingly, New Jersey leads the nation in the proportion of millennials who live with their parents – 46.9% of people 18 to 34 years old, which is considerably higher than the national average of 34%.9 New Jersey millennials are also more likely than other age groups to leave the state, which creates gaps in the workforce and challenges for New Jersey’s economy.10

Availability and affordability issues force New Jersey to struggle with continued patterns of suburban sprawl and racial and socioeconomic housing segregation. Despite progress made through the state’s Fair Housing Act and State Planning Act, municipal land-use zoning has resulted in increased segregation and sprawl statewide.11 According to data from the 2010 Census, New Jersey has the sixth highest level of Hispanic/ white residential segregation in the nation, and the 11th highest level of black/white residential segregation.12

New Jersey is the most densely populated state and the most built out. More than 2 million of the state’s 5 million acres are fully developed, and an estimated 1.4 million acres are protected. With much of the remaining land unsuitable for development, researchers expect New Jersey to approach near-total build-out by midcentury.13 Time is running out to conserve vulnerable natural resources and make the necessary investments in housing and communities.

With 565 self-governing municipalities—83 more than in California, even though New Jersey’s entire footprint fits into 5% of California’s land area—New Jersey suffers from “multiple municipal madness.”14 This condition exacerbates already high property taxes and encourages a convoluted “ratables chase” for new commercial and industrial development tax revenues while discouraging residential development, particularly homes that might attract families with school-age children.15 These development patterns also contribute to long commutes and high transportation costs. New Jersey residents travel farther for work than residents of every other state except New York and Maryland16 and people who live in the New Jersey-New York-Connecticut region face the nation’s fourth highest commuting costs.17 While New Jersey has an extensive transit infrastructure – NJ Transit has 166 stations located along 12 lines in suburban and urban centers – the state has not maximized development potential around these strategic locations nor has it extended rail service in densely populated corridors.18

As if these challenges were not enough, Superstorm Sandy dealt a devastating blow to New Jersey in 2012, compounding damage the state suffered during Hurricane Irene the previous year. The destructive coastal flooding and extensive inland flooding made evident the vulnerability of so many homes and, in some cases, entire neighborhoods. The risks of climate change are not hypothetical to state residents; indeed, Sandy destroyed or severely damaged more than 40,000 primary residences and 15,000 rental units,19 and did more than $30 billion in damage in New Jersey.

The Garden State is in a bind. New Jersey has too few homes that residents can afford, legacy consequences from sprawl, aging infrastructure, and a geography that makes its land particularly vulnerable to the encroachment of rising seas. At the same time, the state’s resources and its political will to address these challenges have diminished.

Fortunately, New Jersey has a strong legal and historical framework for addressing the dual challenges of housing affordability and sprawl. It has the opportunity to capitalize on recent demographic trends, extensive transit infrastructure, and a favorable geography with proximate access to the employment centers of New York and Philadelphia. And the state has every incentive to lead. Tackling these challenges and opportunities head-on would provide tangible economic benefits to New Jersey’s residents, communities, and businesses.20 Specific solutions are offered in the four sections below. The time to embrace progress is now.