For years, decisions about whether people charged with crimes would be released from jail pending trial were based on a defendant’s financial resources. Judges set bail—an amount of money, which, if posted, allows defendants to be released—designed to ensure that defendants appeared in court. This process resulted in people with low financial resources being punished in two ways. First, when defendants and their families were able to scrape together the money, often thousands of dollars, required to post bail, they typically would not get the money back even if the defendant appeared in court as required.36 Although some people could post bail directly with a court and receive their money back at the end of the case, most people were forced to use commercial bail bond companies that kept any money paid regardless of the outcome of the case.37 Second, people who were unable to post bail would languish in jail for months, or even years. Confronted with the option of either staying in jail or pleading guilty and getting out of jail, many people opted for the latter, even if they were innocent.38

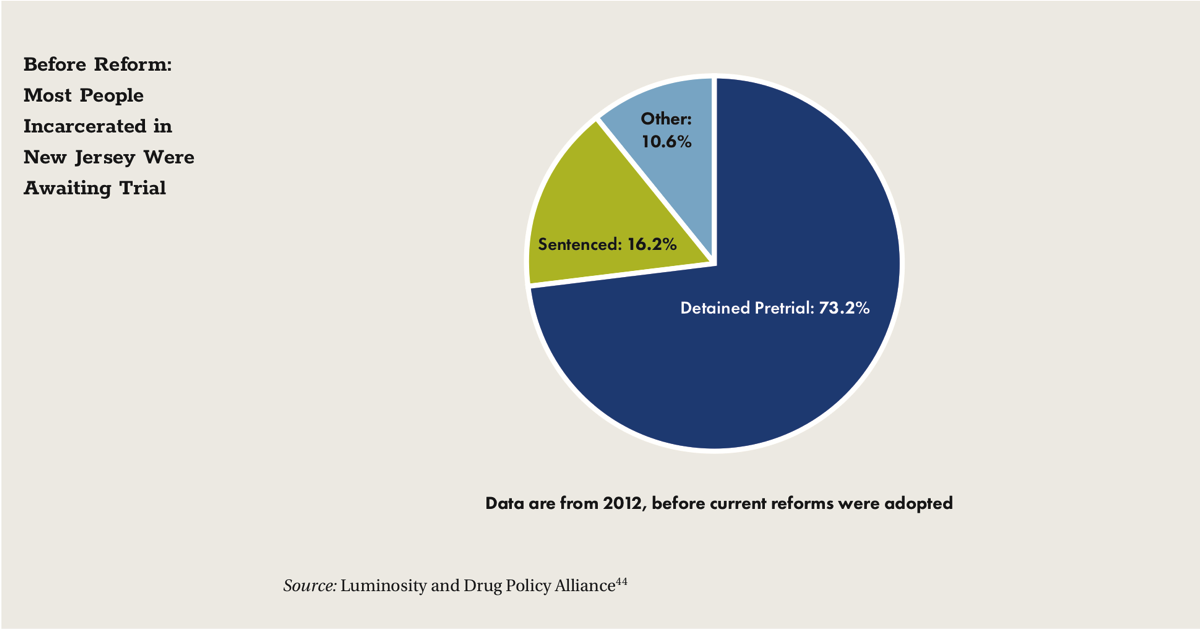

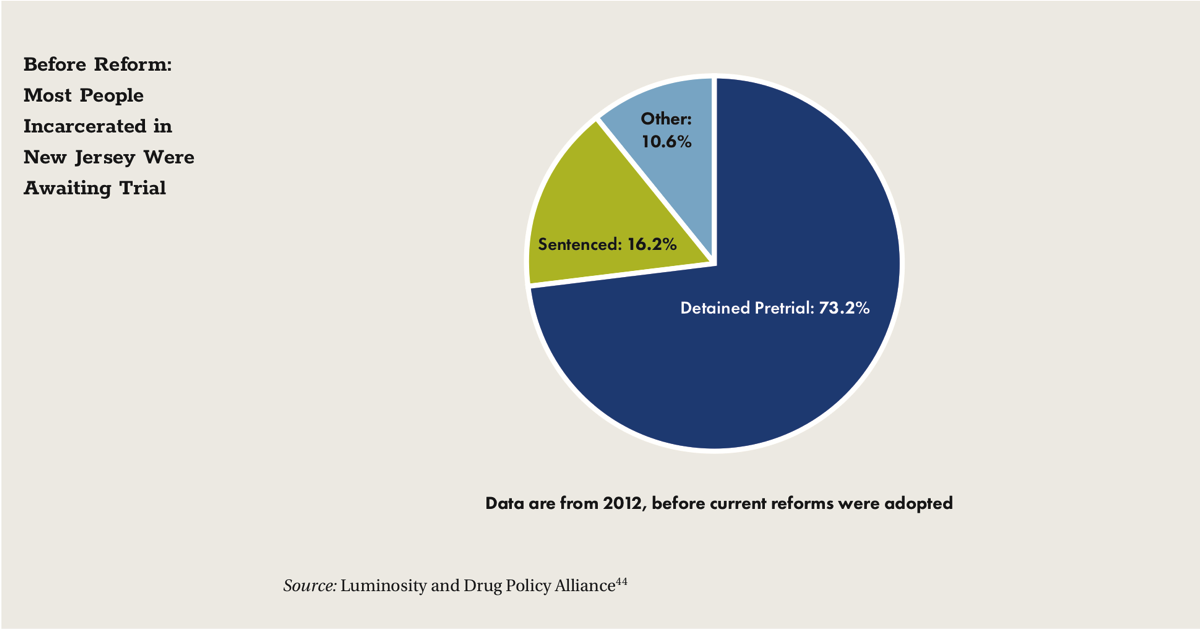

A 2013 study concluded that, on a single day, more than 5,000 people—38% of the 13,000 in custody at the time—were in New Jersey’s county jails because of inadequate financial resources. And 33% of those detainees (more than 1,600 people, 12% of the entire jail population) could have secured release for $2,500 or less. The average length of stay in jail pending trial was about 10 months, which generated significant and unnecessary costs for the state.39 The report also showed the disparate impact on minorities: 71% of people in New Jersey jails were Black or Latino.

The devastating effects of incarceration, even for a few days,40 on individuals, families, and communities have been well documented. Even if not tried and convicted, jailed people suffer consequences of incarceration and risk losing their jobs, falling behind on household bills, and even losing custody of their children.41

The 2013 study spurred action, first by the state Judiciary42 and later the Legislature. In 2014, New Jersey passed historic legislation designed to tie pretrial detention to the danger the defendant would pose to the community, rather than to whether the person had enough money to make bail. In other words, the new statute was designed to move from a resource-based system to a risk-based system. That change was critically needed because New Jersey’s jails were filled with people who presented a low risk of committing subsequent crimes and were eligible to be released while awaiting trial except that they lacked the money to post bail.43

The reform law took effect January 1, 2017, two months after voters approved a related state constitutional amendment.45

If properly implemented, pretrial justice reform can dramatically reduce the population of New Jersey’s county jails.46 Indeed, the reform already shows great promise. New Jersey’s pretrial jail population declined by more than 20% in the first six months of 2017.47

Although pretrial justice reform is in place, it is still subject to attack, including by those with a financial stake in the old, unfair system. The next governor must protect and strengthen the state’s historic reforms.

LIMITING PREVENTIVE DETENTION

Under a risk-based system of pretrial release, when a court determines that a defendant’s release pending trial would pose an unacceptable threat to public safety, the court is authorized, after conducting a hearing, to detain that person. Though preventive detention, as it is known, is constitutionally permissible,48 it puts a strain on the presumption of innocence. State law responds to this concern by permitting preventive detention only when a court finds that no set of conditions can adequately protect the public, prevent obstruction of justice, and ensure the defendant’s presence at court hearings.49 In determining whether detention is proper, there is a presumption against detention in all cases except when the defendant is charged with murder or another crime carrying a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.50

In 2016, opponents of bail reform suggested that lawmakers expand the category of cases for which preventive detention would be presumed, to include all crimes of violence.51 Although some elected officials and law enforcement personnel agreed,52 doing so would make detaining people far easier and more common and, thus, would undermine the aims of reform.

Where a defendant is actually a danger, a prosecutor should be able to make a showing relying on the specific facts of the case or history of the defendant, rather than the nature of the charge. When a person is forced to stay in jail because of perceptions arising from an unproved charge rather than proof that he or she poses a future danger, we have a serious challenge to the presumption of innocence. In rare cases, detention may be necessary, but New Jersey should not make it easier for prosecutors to utilize this exceptional remedy.

RECOMMENDATION

Resist efforts to expand categories of cases where courts presume detention.

Detention should be permitted only where the trial court finds detention is necessary to achieve the purposes of the pretrial justice reform law. Efforts to increase incidences of detention must rest on rigorous data collection and analysis.

Do not reintroduce money bail as the primary mechanism for pretrial release.

Money bail will not reduce the number of pretrial detainees, make the system fairer, or save money. Although opponents of bail reform point to the cost associated with screening defendants and running pretrial services,53 the costs are more than offset by the savings—and increased fairness—associated with reduced pretrial jail populations.54

Update New Jersey’s speedy-trial framework so that no defendant waits in jail for two years or more to have his or her case heard.

For the first time, the pretrial reform law provided New Jersey with a statutory speedy-trial framework. Defendants who are detained are guaranteed an opportunity to go to trial within a specified period.55 This is a welcome change, as New Jersey had long been among a minority of states in which time limits were not explicitly set by either law or court rule.56 But the periods set forth in the New Jersey statute are still too long. Defendants may have to wait in jail for longer than two years for a trial, even in relatively simple cases.57

AVOIDING RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN THE PRETRIAL JUSTICE SETTING

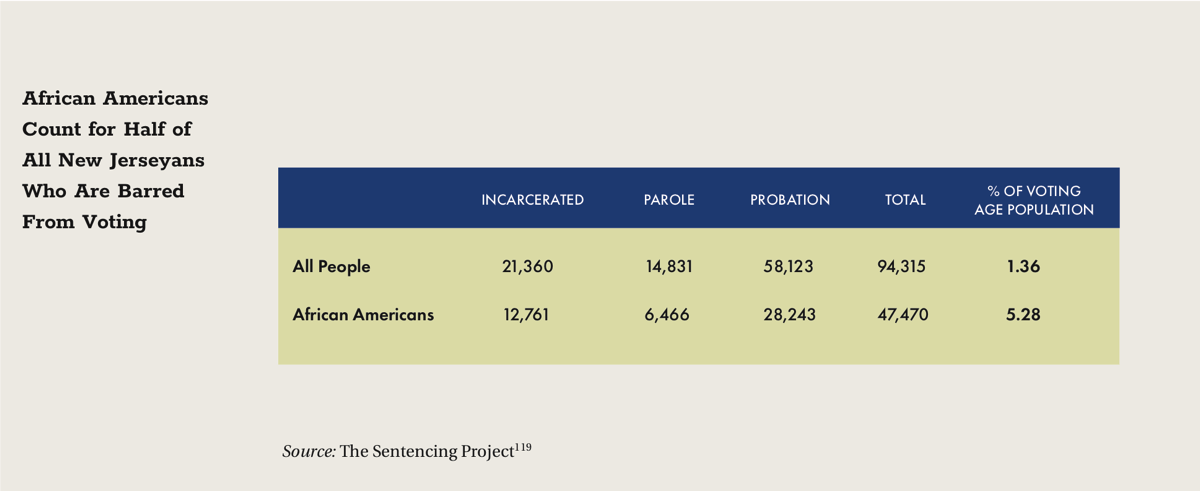

The pretrial justice reform statutes require that the assessment tool used to predict risk “not be discriminatory based on race, ethnicity, gender, or socio-economic status.”58 But many experts have warned that, if not properly validated or used, risk assessment tools could further the racial disparities in the criminal justice system.59 Even when properly used, those tools often rely on arrest and conviction data that, in turn, are based on our current system—in which people of color are disproportionately targeted for arrest and prosecution. The result is a continuing cycle of inequality.60

The racial impact of pretrial justice reform requires ongoing evaluation to ensure the changes have no racially discriminatory effect and that, indeed, they reduce the discrimination that pervades the justice system.

RECOMMENDATION

Rectify serious racial disparities in the criminal justice system through efforts to calibrate the pretrial justice risk assessment.

All risk-assessment tools contain value judgments. Is the tool more concerned with failure to appear or new criminal activity? Does the tool treat all new criminal activity the same, or is it more concerned with certain crimes? New Jersey’s tool should be designed to reduce rather than exacerbate racial disparities and should be evaluated regularly to achieve that purpose. One way to accomplish this is by giving less weight to inputs (marijuana possession arrests, for example) known to involve significant racial disparity.