The nature of New Jersey’s energy supply and demand poses serious challenges to the effort to reduce harmful emissions.

New Jersey’s electricity portfolio, when last reported in 2015, included 49.5% that was generated through the use of natural gas.

Nuclear plants provided 44.5%, and only 2% came from coal. Coal usage, which has been declining sharply since 2006, now is close to zero: in June 2017, Public Service Electric & Gas closed the state’s two largest and oldest remaining coal-fired power plants, leaving two smaller plants.

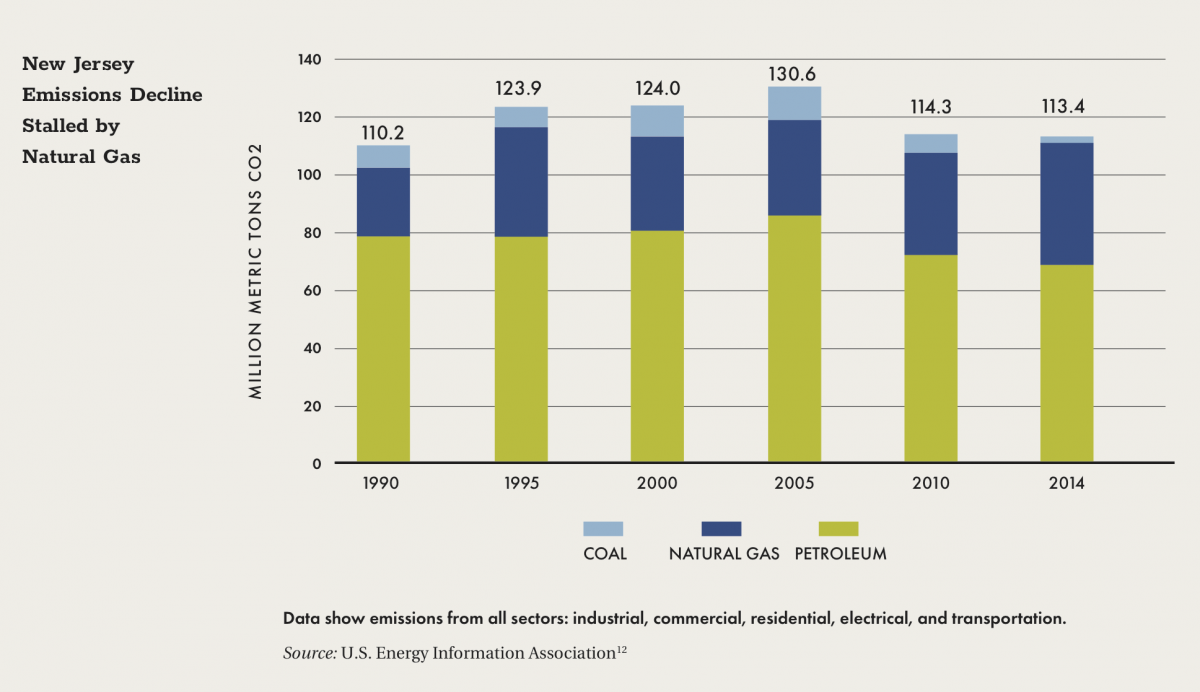

Despite that, overall emissions from energy generation declined by only 8% from 2006 to 2015.10 Heavy reliance on the burning of natural gas was the reason the drop was not greater. Gas-fired generation in New Jersey increased dramatically—by 51% from 2013 to 2016 (surpassing nuclear power)—and that brought a significant increase in carbon dioxide (CO2) from combustion.11 When methane emissions from natural gas are taken into account, the situation became even more serious, given that methane is a more potent greenhouse gas than CO2 in the short run.

The trend away from nuclear power is likely to accelerate when the Oyster Creek nuclear plant, responsible for about 4% of in-state generation, closes in 2019.

PSEG has raised concerns about the financial viability of its nuclear plants in New Jersey. For New Jersey, then, emissions reductions from electricity production is a matter of reducing natural-gas generation while substantially improving efficiency and increasing renewable energy production.

On the demand side, New Jerseyans’ energy consumption is lower than the national average. The state ranks 37th in per-capita energy consumption.13

LIMITING CARBON EMISSIONS

New Jersey was once among the leading states in a cooperative effort to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, which included the “California Car” program, the 2007 state Global Warming Response Act, the 2008 state Energy Master Plan, and a regional cap-and-trade14 agreement. The state was among seven that in 2005 established the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative,15 the nation’s first mandatory cap and trade program. States participating in RGGI commit to capping their carbon emissions and requiring power plants to purchase allowances in order to emit specific amounts of carbon. Three more states joined in 2007. Then New Jersey dropped out in 2011.

RECOMMENDATION

Rejoin the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

RGGI has proven to be a useful way to reduce carbon dioxide levels and promote energy efficiency. RGGI participants allocate CO2 allowances largely through regional auctions that generate money for the states to reinvest in energy-saving programs. Through 2014, states used nearly $1.4 billion in this way, with each state deciding how to spend its share. New York, for example, in 2016 launched a $16 million initiative that helps municipalities reduce energy consumption and promote clean energy use. Since RGGI began, power sector pollution is down 45% in the participating states.

If New Jersey rejoined RGGI, it should dedicate a stated share of funds from CO2 auctions for use in urban areas and communities of color where harm caused by pollution is greatest. In addition, a 25% reduction in emissions should be mandated for power plants located in such neighborhoods.

PROMOTING CLEAN ENERGY

The safest, most efficient energy future for New Jersey is clean, renewable energy such as wind and solar, combined with reduced energy waste. The state Senate has twice voted overwhelmingly to enact the Renewable Energy Transition Act. RETA would require that 80% of all electricity sold in the state “shall be from Class I renewable energy sources” by 2050. Class I sources include solar photovoltaic, wind, and methane gas from landfills.

RETA sets up a schedule of increases, starting with 20% renewables by 2020 and increasing the target by 10% every five years, reaching the full 80% level by 2050. The amount of electricity sold in the state from renewable sources—nearly zero just 10 years ago—is currently less than 10%.

Enactment of RETA would make New Jersey one of the leading states in the use of renewables. The California Senate has adopted legislation to speed its transition to 50% renewable energy by 2026 and to move to 100% renewable energy by 2045. Hawaii enacted a 100% renewable energy mandate by 2045. New York is committed to achieve 50% renewable energy by 2030.

RECOMMENDATION

Mandate that 80% of all electricity sold in the state comes from renewable sources by 2050. Pass the Renewable Energy Transition Act to move immediately toward this mandate.

LONG-TERM ENERGY PLANNING TO MEET EMISSION TARGETS

Chief among existing New Jersey state laws addressing climate change is the Global Warming Response Act (GWRA), passed in 2007. It calls for reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020, and sets a target of further reducing emissions to 80% below 2006 levels by 2050. The state is not on track, nor does it have a plan, to meet the 2050 goals. In fact, as already noted, emissions reductions in the electricity generation sector have slowed due to the significant increase in gas-fired electric generation.

The law would be even more effective if it set specific targets for increased renewables such as wind and solar and for reduced energy use.

RECOMMENDATION

Require a Clean Energy Master Plan, to be updated every five years, that establishes a pathway to achieve the statewide target for 2050. It should include analysis and interim emissions targets by sector for 15 years.

Adopt a measurable, accountable energy-saving goal of 30% below 2015 levels for electric and natural gas usage in New Jersey by 2030.

This goal is to be reached by reducing residential, commercial, and industrial energy consumption; reducing vehicle miles and increasing the proportion of low- and zero-emission vehicles on the road; shifting from fossil fuels to renewable sources (solar, wind, geothermal); and fostering land-use patterns that preserve and protect open space, tidal marshes, and forests.

MAKE ENERGY EFFICIENCY A WAY OF LIFE

Climate change and other 21st-century considerations require giving more attention to how the places where New Jerseyans live and work are built and operated.

RECOMMENDATION

Establish an Energy Efficiency Portfolio Standard that requires utilities to meet a minimum level of energy efficiency each year and includes incentives to achieve higher energy efficiency gains.16

As of January 2017, 26 states had fully funded policies in place, with specific energy savings targets that utilities or non-utility program administrators must meet through customer energy efficiency programs.

RECOMMENDATION

Increase minimum energy efficiency standards for household and commercial appliances, codified in law and regulation; and update state construction code standards for new commercial and residential buildings.

Set a goal to accelerate wider-scale development of “net zero” homes and buildings — those where the amount of energy consumed yearly is about the same as the amount of renewable energy created there.

An aggressive policy would require all new homes built in the state to be net zero by 2020, and all new commercial buildings by 2030.

MAKE STATE GOVERNMENT A STRONGER PARTNER

Energy efficiency is important enough to be promoted more actively at the state level.

RECOMMENDATION

Establish a state agency or authority to drive energy efficiency measures, monitor and evaluate the success of current and future measures, and develop innovative ways to reduce energy use.

Such an agency should prioritize low-income communities.

State officials also could play a larger role in helping residents learn about and prepare for job opportunities that can come from energy efficiency.

Create a statewide hub for “green jobs” training, modeled on successful programs in Trenton and Newark.

Examples of green jobs include stormwater management, cleaning up “brownfields” for reuse, urban forestry, and assessing buildings to see whether they meet energy efficiency standards. This effort could leverage federal and state job-training funds and involve renewing the state tax credit for employers that hire graduates of the program.

DEALING WITH VEHICLE POLLUTION

Greenhouse gases also originate from mobile sources, primarily motor vehicles. At least until the new administration took over, the U.S. Department of Transportation had steadily toughened Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards to meet more stringent greenhouse gas emissions standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. New Jersey, in turn, adopted the California Car program,17 requiring passenger vehicles and light-duty trucks sold after Jan. 1, 2009, to meet the EPA’s strictest vehicle emissions standards, and creating incentives for Zero Emission Vehicles.

Regardless of where federal policy goes next, the improved fuel efficiency of cars and the increasing number of low- and zero-emission vehicles on New Jersey’s roads show the effectiveness of the CAFE standards and the California Car program. Their salutary effect, however, is at least partially offset by steady growth in miles traveled by New Jersey motorists: 75.4 million miles in 2015, compared with 72.8 million in 2009.18

RECOMMENDATION

Expand electric car infrastructure by participating in the regional Transportation and Climate Initiative on electric vehicles, and support proposed expansion of CAFE standards for cars and light trucks during the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration program review.19

The Transportation and Climate Initiative is a collaboration of 12 Northeast and Mid-Atlantic jurisdictions that seek to develop the clean energy economy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the transportation sector. CAFE standards are adopted pursuant to the law that Congress passed in 1975 to improve average fuel economy of cars and light trucks manufactured for sale in the U.S.

Accelerate expansion of fast charging stations for electric vehicles on the state’s roadways, modeled on the U.S. Department of Transportation’s “alternative fuel corridors” initiative.

New technology requires commitment of state resources. Gas stations along highways are of no use to owners of electric cars, and electric car infrastructure is a must if such vehicles are to help address New Jersey’s pollution problems.

HARNESSING WIND FOR POWER

The Offshore Wind Economic Development Act, adopted in 2010, authorized the state Economic Development Authority to provide tax credits for qualified facilities in wind energy zones. There has been no effort to implement this law, however— costing New Jersey jobs, renewable energy, and investments that offshore wind projects generate in other states. New Jersey has significant potential generation capacity, and with greater support from policymakers the state is positioned to be a national leader on offshore wind projects.20

RECOMMENDATION

Take the necessary steps to move ahead with offshore wind projects, including creation of Offshore Wind Renewable Energy Credits as the financing mechanism necessary for investment in wind projects.

Other states already have begun awarding ORECs. New Jersey needs to catch up, starting with a definitive evaluation of the potential for offshore wind, including capacity, preliminary siting scenarios, and an economic analysis to determine the cost to utility consumers. The Offshore Wind Economic Development Act mandates that the Board of Public Utilities take into account the cost of a project and conduct a cost-benefit analysis. The bid process and the cost of ORECs will provide a clear snapshot of the expected cost of the project for utility customers. BPU’s analysis should examine the outright cost of the energy as well as the social cost of carbon (including projected sea-level rise). This calculation would offset the higher initial cost currently of renewable energy with the future cost of fossil fuel energy, and would factor in cost-reductions in the clean energy technology.

With the goal of reaching 3,000 megawatts of offshore wind by 2025 and 5,000 megawatts by 2030, an ongoing comprehensive ocean planning process will inform decisions on siting and size.

PROMOTE CONTINUED DEVELOPMENT OF SOLAR POWER

New Jersey has been a nationally recognized leader in solar power development, ranking first on the East Coast and among the top three states nationwide in installed solar capacity. In 2015, solar power became the state’s largest source of renewable electricity.

New Jersey should promote additional growth in solar by considering policies that other states have recently implemented to foster the solar market. For example, New York implemented a public/private partnership, called NY-Sun, that coordinates and expands existing solar programs, including that of PSEG Long Island, to support solar expansion. The cost of utility grid solar has significantly decreased in New York. Delaware and Connecticut now use a bidding system for inclusion in long-term contracts, with some solar companies bidding zero charges for the first three or four years to gain the security of the longer term.

RECOMMENDATION

Expand solar to about 15% of New Jersey’s energy mix by 2030, and help reach that goal by adopting a program to reduce costs to residences and businesses.

Direct New Jersey’s Board of Public Utilities to undertake a comprehensive review of best practices nationally and make recommendations for further strengthening and expanding New Jersey’s solar capacity through a public process.

USE CLEAN ENERGY FUND AS INTENDED

New Jersey slowed its move to clean energy by diverting more than $1.3 billion that utility customers had paid into programs designed to reduce energy use and promote development of renewable energy sources. These diversions for other purposes continued under the state budget adopted for the fiscal year starting July 1, 2017.

RECOMMENDATION

Use money from the Clean Energy Fund exclusively for energy efficiency, clean energy projects, and innovative clean energy technologies.

Raiding this fund and others is a counterproductive practice that delays a meaningful solution to the state’s fiscal problems and sets back efforts to improve residents’ well-being in important areas. This needs to stop. If legislators and the governor summoned the will, they could generate the resources needed for top state priorities.

At least 40% of yearly allocations from the Clean Energy Fund should go to energy efficiency and renewable energy projects in New Jersey’s urban areas and communities of color.

PIPELINE PROLIFERATION

New Jersey’s increased reliance on natural gas for electricity has serious drawbacks. Though natural gas burns more cleanly than oil or coal, it is a non-renewable fossil fuel, with high levels of carbon dioxide, and it brings a dramatic increase in emissions of methane—a powerful greenhouse gas that absorbs 25 times as much heat as CO2 does. In addition to the climate impact, there are direct local effects: some power plants fueled by natural gas, including the Newark Energy Center, are in economically distressed neighborhoods and communities of color, where they contribute to air pollution that already is at disproportionately high levels.

A growing share of the natural gas reaching New Jersey comes from hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) in Pennsylvania. To carry this product from source to end users elsewhere in the U.S. and overseas, new pipelines have been proposed for New Jersey. Already, 1,520 miles of pipelines crisscross the state. Serious questions have been raised about the dangers these pipelines pose to public health and ecologically sensitive lands and habitat—explosions, as well as accidents, leaks, and spills—as well as about whether more pipelines are being proposed than needed to meet demand.

RECOMMENDATION

Place a moratorium on all pending pipeline projects and conduct a review to determine whether they are necessary, safe, and consistent with the state’s goals to reduce the adverse impacts of climate change.

Such an assessment would include determining pipelines’ impact on New Jersey’s ability to meet targets under the Global Warming Response Act.

Ensure that pipelines do not damage critical natural resources, by using the state’s full authority under the Clean Water Act and state regulations.

This would help prevent the approval of projects that are inconsistent with the regional plans protecting the Pinelands and the Highlands.