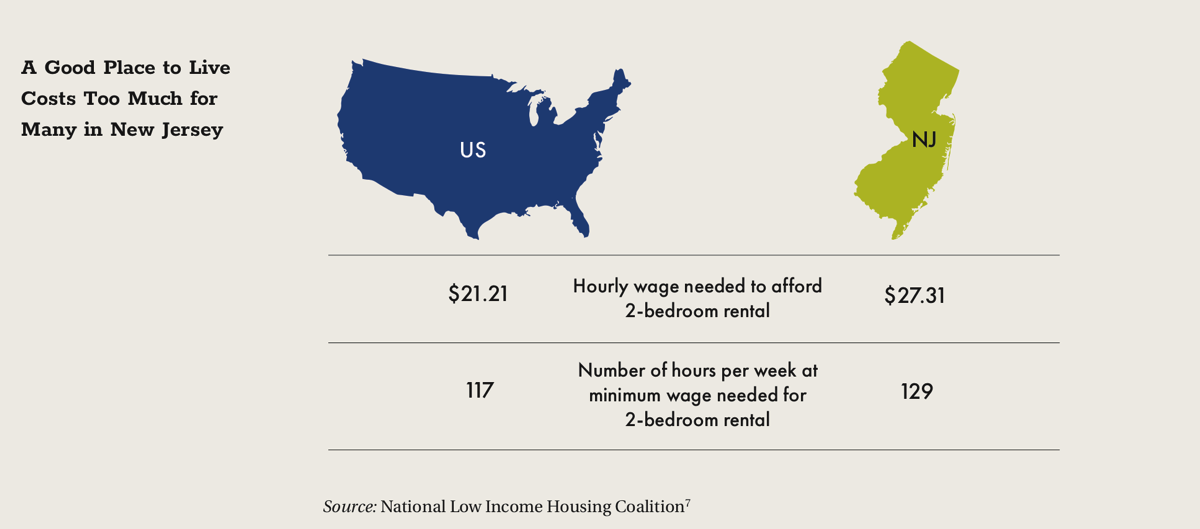

Substantial research conducted in recent years demonstrates the links between stable, affordable homes and positive outcomes for families and children. When families pay more for housing than they can afford, every other part of a household budget suffers.

Affordable housing has been linked to better healthcare access and decreases in Medicaid health care expenditures as those who can afford their homes use preventive care rather than more costly emergency department visits.21 Stable, affordable homes lead to better nutrition, healthy brain development, and lower rates of child hospitalization for low-income families and children. Those with affordable housing also spend more on their children’s enrichment than those without, leading to stronger child cognitive development.22

Families lacking a stable, affordable home, in contrast, are more likely to struggle to feed all members of the household adequately, to have utilities shut off, and to forgo needed health care.23 A Boston College study found that poor housing quality, followed by residential instability, was the strongest predictor of emotional and behavioral problems among low-income children.24

Increasing the supply of affordable homes is also critical to putting New Jersey’s economy back on track. A recent national study found that building 100 multi-family homes generates $11.7 million in local income, $2.2 million in taxes and other revenue for local governments, and 161 local jobs in the first year.25 In New Jersey, the affordable housing and community revitalization work done by community development organizations alone added $12 billion to the state’s economy over the last 25 years, or approximately $500 million per year.26 An analysis of New Jersey’s Special Needs Housing Trust Fund determined that the $200 million state investment in permanent supportive housing created 8,800 one-time jobs, 1,600 ongoing jobs, $576 million in worker income, $14.4 million in state sales tax revenues, $1.75 million annually in state income taxes, and $10.4 million per year in local property tax revenues.27

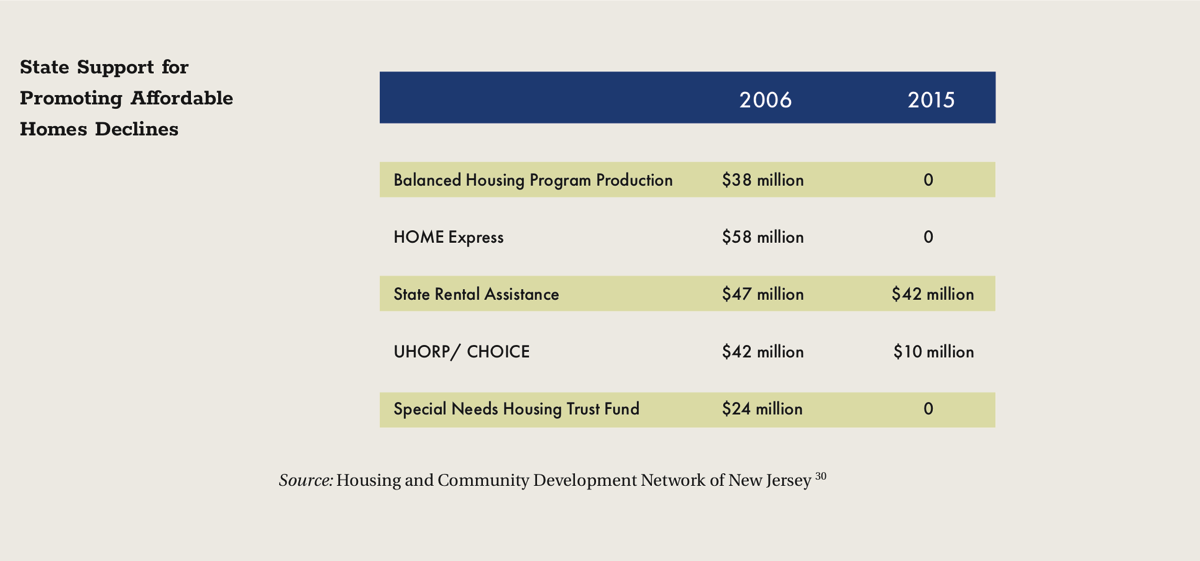

When families struggling to get by can spend more of their hard-earned pay on consumer goods and services than on housing costs, the economy benefits. Unfortunately, too many New Jerseyans today must pay more for their homes than they can afford, leading households to forgo other necessities and contributing to chronic housing instability and homelessness. Yet, despite the demonstrated need for, and the economic and societal benefits of, affordable homes, state investment in affordable homes in New Jersey has dwindled over the past decade.28

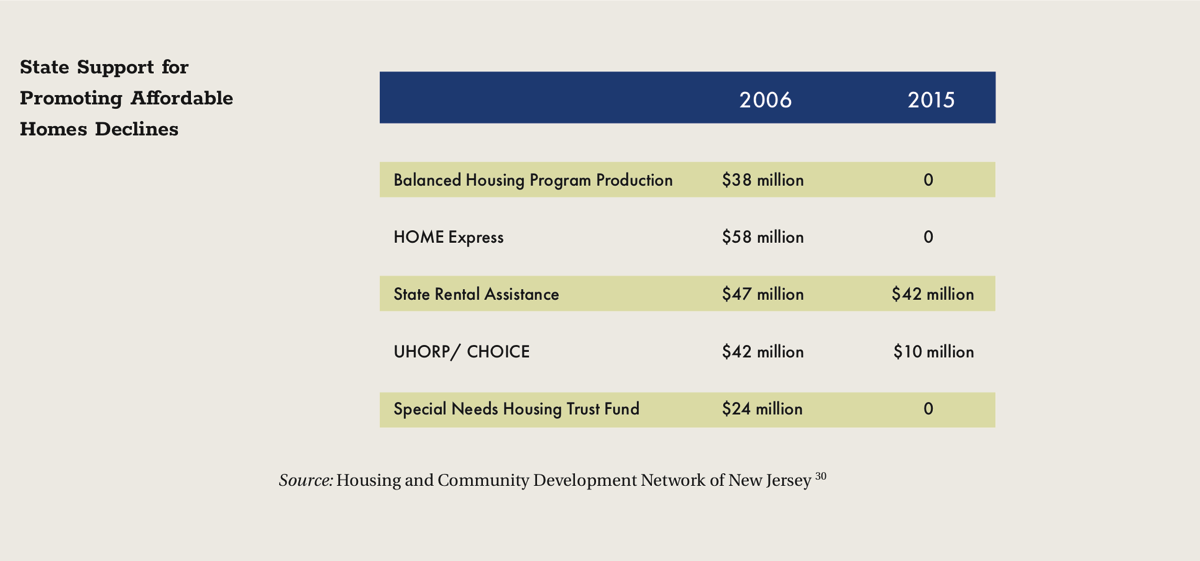

Some examples are telling.

In 2009, Balanced Housing funds (now called the Affordable Housing Trust Fund) were used to produce 260 homes in New Jersey; in 2013, that figure was 96.29 Money for this initiative came from the state’s realty transfer fees. Funds collected that should have been dedicated to the Affordable Housing Trust Fund for the purpose of producing affordable homes have been diverted in the state budget to pay for rental assistance and other non-housing production programs; these other programs previously had been financed through the state budget’s General Fund. Last year alone, $52 million was diverted.

Also zeroed out of the state budget in 2015 was another major initiative, HOME Express, which streamlined the process for developers applying for both state and federal funds. Many other useful forms of assistance were reduced. The State Rental Assistance Program was cut to $42 million from $47 million at the same time that rents were increasing. And, CHOICE, which offers comprehensive financing for developing new and substantially rehabilitated homes in areas where market rate home values are too low to support new construction, was cut to $10 million in 2015 from $42 million in 2009.

STRATEGICALLY TARGETING RESOURCES

The state’s recent lack of support in these areas is a distressing ledger. Each of these funding cuts takes a toll as it takes away support that helps more people own or rent a home, participate in the economy, and gain a greater personal stake in the community.

RECOMMENDATION

Adopt the Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey’s “Build a Thriving New Jersey” plan31 to strategically invest $600 million to help more state residents find good, affordable places to live.

The package would direct resources, many of which have been diverted to other purposes, to increase the supply of affordable homes for working families, seniors, and people with disabilities. This level of investment would help address the need for hundreds of thousands of new and affordable homes identified through the Mount Laurel process.

The proposed funding levels are based on what is needed to meet the high current demand and to make up for nearly a decade of lost funding. Through an increase in the Neighborhood Revitalization Tax Credit and full funding of other programs, these strategies also would encourage mixed-use and transit-oriented development where infrastructure exists or could be enhanced. Resources would be available to improve the state’s older housing stock—which would benefit public health, especially by reducing the danger of lead poisoning—and to promote development of homes near where people work. New revenue, enhanced nonprofit capacity, and new public-private partnerships would make possible a mix of rental homes and home ownership opportunities. Significant funds would be dedicated to providing stable homes for people who are homeless and people with special needs.

Revenues for the $600 million initiative could come from a variety of sources, including general revenue, matching federal funding, realty transfer fees charged on the transfer of property, and NJ Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency (NJHMFA) lending. Previously, the NJHMFA bonded for the Special Needs Housing Trust Fund but those resources have been exhausted.

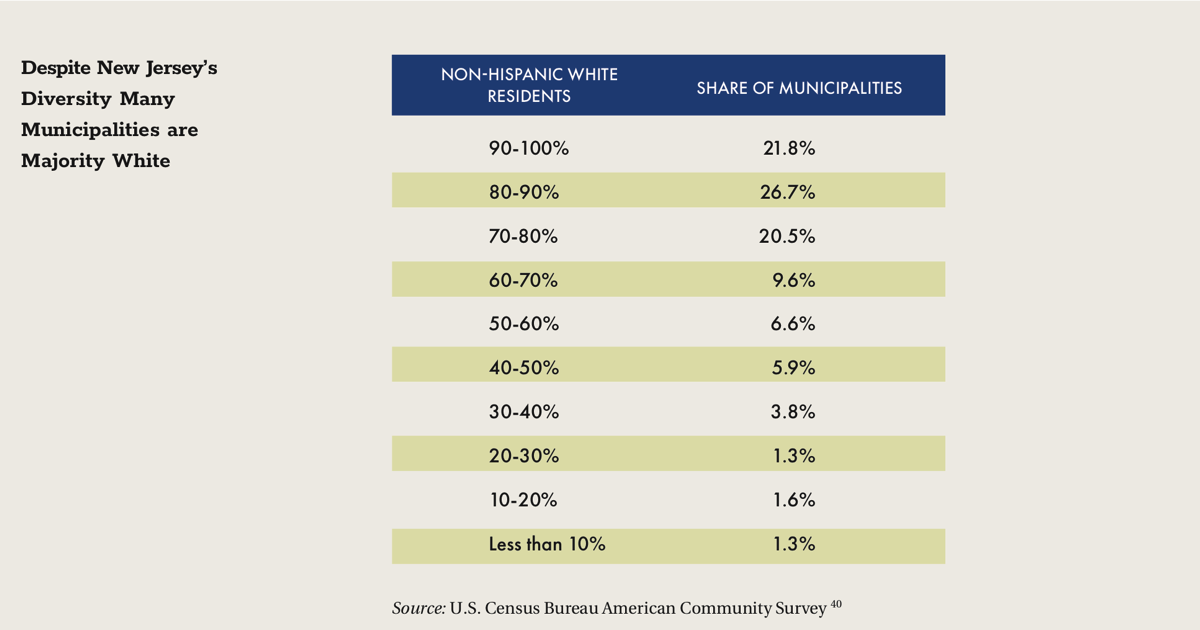

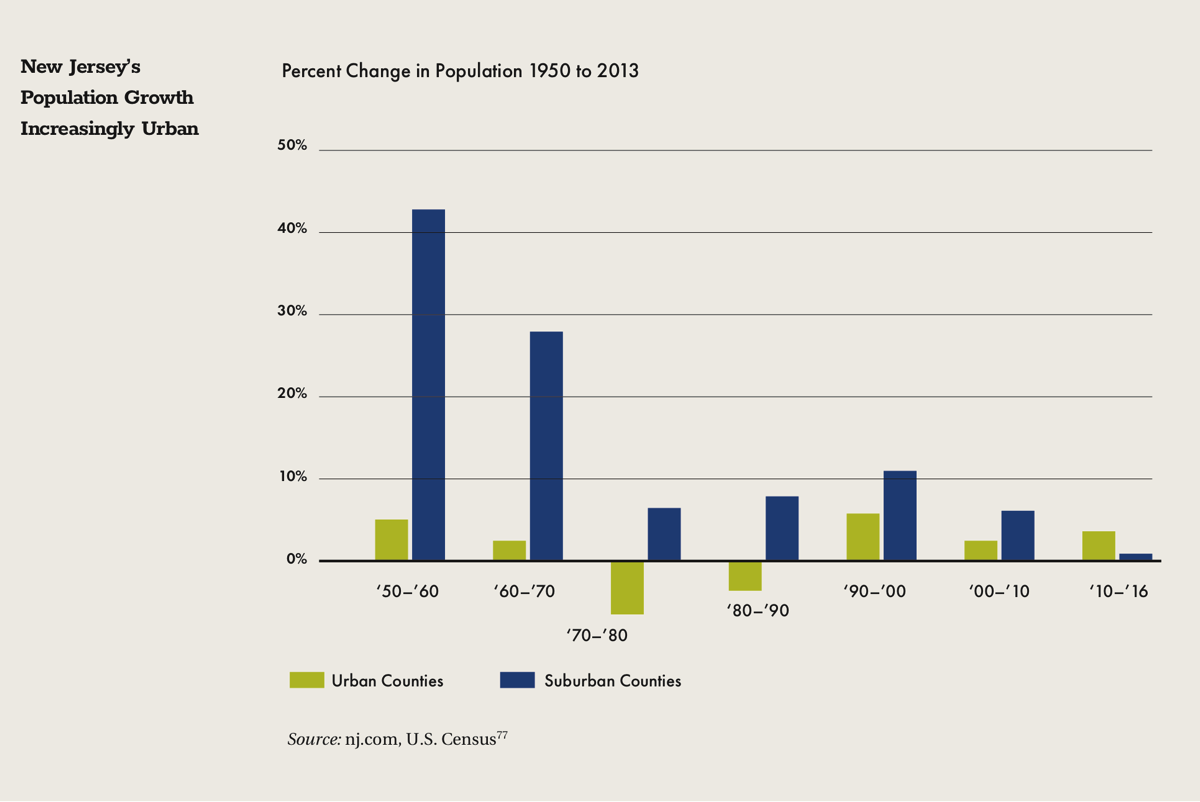

SUPPORTING MIXED-INCOME HOUSING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN URBAN AND DOWNTOWN AREAS

While many New Jersey cities continue to struggle to attract private sector investment, others, such as Jersey City and Hoboken, are experiencing downtown and neighborhood revitalization and private investment in business and real estate. With such investment, however, housing costs often go up, with the result that lower-income residents are priced out of those communities. In such strong housing markets, inclusionary development policies can help ensure that lower-income as well as upper-income residents share in the benefits of economic revitalization. State investment in struggling communities can also have benefits such as to stabilize neighborhoods and encourage 24/7 vibrant downtowns. Maximizing opportunities around transit stations is key both to revitalizing and supporting economic growth in these centers as well as creating opportunities for inclusionary residential and mixed-use development so people can easily access jobs and cultural opportunities.

RECOMMENDATION

Grant state and regional agencies the authority to approve projects of regional significance.

Relevant state and regional agencies should have the authority to override local zoning and approve significant projects that are consistent with the agencies’ adopted plans and regulations and when warranted by major infrastructure or other public-sector investment, including investment of state funds. Examples of approvals that would be appropriate are transit-oriented development projects that provide excellent access to jobs and the inclusion of affordable homes in areas designated for growth by a regional plan.

Adopt inclusionary zoning ordinances in cities with strong real estate markets to foster equitable, inclusive communities and enable lower-income residents to live near work and schools.

Such inclusionary zoning ordinances could apply to an entire city or could be strategically targeted to particular neighborhoods or downtown areas that are experiencing the most investment. Such policies help manage gentrification and encourage balanced revitalization as investment comes back to some of New Jersey’s cities.

Provide tax credits for developers to build affordable mixed-inc ome homes in economically distressed areas to revitalize communities and provide good-quality homes.

One proposed initiative would provide up to $600 million in such credits for development where median family income does not exceed 80% of statewide or applicable metropolitan median family income, and it would also address the needs of residents with lower incomes.32 The goal is to create thriving residential neighborhoods in areas dominated by offices and 9-to-5 activities.

PROVIDING FOR THE HOMELESS AND THOSE WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

The 2008 recession brought a statewide increase in homelessness. Although the number of homeless men, women, and children in New Jersey is down by almost half over the past decade, nearly 9,000 people still lack reliable shelter.33 Further, many more households are on the brink of homelessness due to New Jersey’s high housing costs and the crisis in evictions and foreclosures. Among families making less than $26,030 a year, 74% spend more than half their income on housing costs—placing them at higher risk of falling behind on rent and becoming homeless.34

A shortage of available public and private funding to provide shelter for people who are homeless or who have special needs has only exacerbated the situation. Nonprofit organizations and private-sector affordable housing developers try to fill the gaps but cannot meet the enormity of the need on their own. Putting together the necessary financing can be dauntingly complex, often involving a maze of federal, state, and local sources as well as tax credits and private loans.

The Special Needs Housing Trust Fund, administered by the NJ Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency and supported by $200 million in state bonding, helped create quality housing with needed supportive services for over 2,000 families and individuals with special needs in all 21 counties. The number of permanent supportive housing units produced by the Special Needs Housing Trust Fund, however, dropped to 126 in 2015 from 482 in 2009.35 When the fund ran dry, no effort was made to replenish it.

RECOMMENDATION

Provide adequate funding for the Special Needs Trust Fund and the State of New Jersey Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program.

The Build a Thriving New Jersey initiative would restore the Special Needs Housing Trust Fund with $45 million in bonding authority through the NJ Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency. The initiative also would allocate $25 million in state General Fund money for homeless programs and $6 million in realty transfer fee revenues as a match for federal homeless support.

New Jersey has a program in place to provide temporary financial assistance and services to households at risk of homelessness.36 With demand so high, the money runs out a few months into each fiscal year. At a minimum, New Jersey should match the $10 million it receives yearly for this program from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Expand rapid re-housing programs to provide housing assistance to any household at risk of homelessness or already homeless.

In addition to providing reliable and predictable funding streams, adoption of a rapid intervention model is key to ending homelessness. Rapid re-housing is an effective intervention that connects uprooted residents to permanent housing through a tailored package of assistance. The fundamental goal is to reduce the amount of time households experience homelessness using a Housing First approach.37